Ibble Gordon, David Crockett, and the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and St. Louis Post Dispatch

Galveston Evening Tribune, February 8, 1894

In late 1893, Ibble Gordon was almost 90 years old. Born in 1805, she came to Texas in 1821 as “a grown woman” and settled along the Red River near Pecan Point. How a story she told came to be printed in the Galveston Daily News and repeated in major newspapers around the United States is unclear, but it demonstrates the power of repetition.

If you have heard my presentation on the treasure legend of Hendricks Lake, you have heard me repeat a quote that “legend remains victorious despite history.” Aunt Ibble’s account may fall into that category. Like most legends, however, it is infused with facts that make it bear repeating.

Mrs. Gordon told the story of how in 1834 she heard that David Crockett of Tennessee was coming to the Red River before heading farther south into Texas. Clarksville had been founded in 1833 and she rode on horseback with another young lady on the saddle behind her about four miles out of town.

That Crockett would detour toward the Red River settlements is unsurprising since the population was largely made up of other Tennesseans. When Aunt Ibble heard he was coming she hoped that he wouldn’t take the “old Trammell trail,” a path that pre-dated the founding of Clarksville by decades.

Ibble and the two young ladies with her were introduced to Crockett. She said he was “dressed like a gentleman and not a backwoodsman.” There was no coonskin cap. She found him to be “a man of wide practical information and was dignified and entertaining.”

Whether Aunt Ibble’s recollections from almost 70 years before her retelling of the story were entirely factual or not is insignificant. Other documentation records that Crockett passed through there and spent some time hunting in the Red River prairies. He enjoyed his time there so much that he wrote his wife about it:

"I expect in all probibility to settle on the Bordar or Chactaw Rio or Red River that I have no doubt is the richest country in the world good land and plenty of timber and the best springs & mill streams good range clear water--and every appearances of health game plenty. It is in the pass whare the Buffalo passes from North to South and back Twice a year and bees and honey plenty.

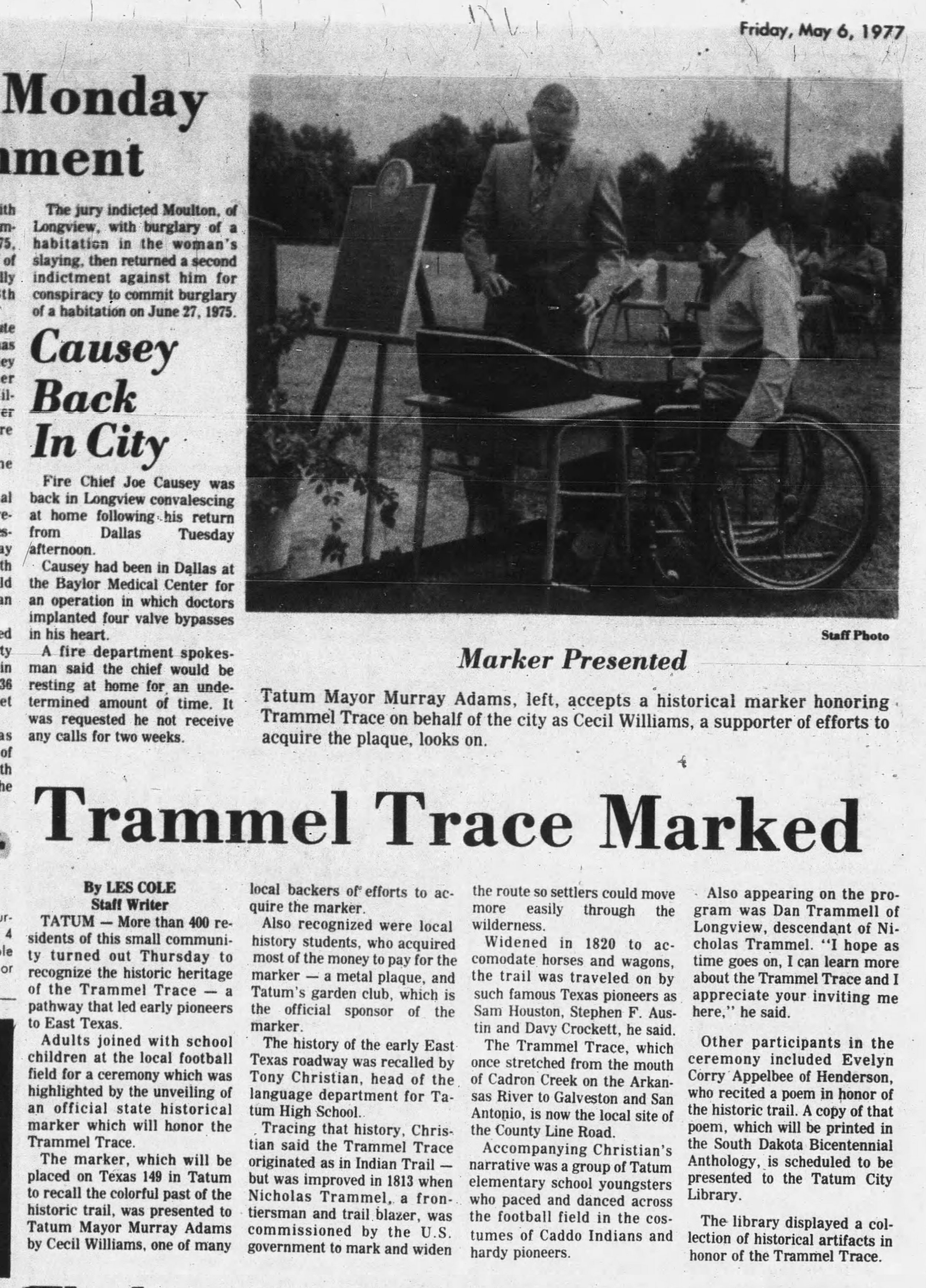

Running across Aunt Ibble’s description of her meeting David Crockett again puts me in a mindset where historical accounts can be more fully appreciated. We know Crockett passed through the Red River. The only way to get from there to Nacogdoches, where a ball was held in his honor, was down Trammel’s Trace.

What makes these reports more intriguing is to put ourselves there. We have been told how Crockett dressed, at least on this occasion. Imagine the house, the smells coming from the kitchen, the voices of what were surely more than a few people anxious to meet famed Crockett. Did Aunt Ibble curtsy or fawn over meeting the well-known Crockett? People likely fell silent when Crockett spoke, and he was not one to shy from that kind of attention.

We can make historic moments more present by re-imagining them as real in our present moment. To be Aunt Ibble on that day would indeed be something worth recording.

Sources:

Polly Ross Hughes, “Davy Crockett's last letter in Texas' hands,” Houston Chronicle. September 5, 2007. https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/article/Davy-Crockett-s-last-letter-in-Texas-hands-1805683.php.

Galveston Daily News, December 17, 1983.

New York Times, January 29, 1894.

Galveston Evening Tribune, February 8, 1894.