Thanks to my brother, Danny, for dredging up this article from a distant corner of the internet. Back in 2007, I met up with Mary Rogers of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram at the Dairy Queen in Tatum, Texas to talk about Trammel's Trace and the Hendricks Lake treasure myth.

We met there for two reasons: 1) The Dude, and 2) they had wi-fi. Here is the text of the feature article she wrote.

SEPTEMBER 16, 2007

Tales of Spanish Silver Lure Treasure Hunters to an East Texas Lake

By Mary Rogers, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Texas

There is something about the idea of treasure hunting that worms its way into the damp folds of the imagination. Legends grow fat there and sing sweet and low of pirates and priests who held plunder in their hands -- then let it slip through their fingers for others to find.

For more than a decade one team of professional treasure hunters heard the siren's call, and earlier this summer Odyssey Marine Exploration hauled up an estimated $500 million in Colonial-era silver and gold coins from a secret trove deep in the Atlantic Ocean. Television crews jockeyed for the best shots as hundreds of plastic jugs filled with the coins were unloaded from a private cargo plane at a guarded location.

And right then, deep in some viewer's mind, the old legends began to sing. I heard them too, as I often do on lazy summer afternoons. But this year I didn't put them aside. I went looking for the lost treasure of Hendrick's Lake, a $2 million fortune in silver allegedly taken from a Spanish galleon by the infamous "Pirate of the Gulf," Jean Lafitte.

The story that fishermen, sometime in the last century, pulled several silver bars from the muddy waters with a hoop net seemed to give this legend legs. The search was to be a lark, a pleasant diversion.

I had no idea what was waiting to be uncovered.

Treasure lore

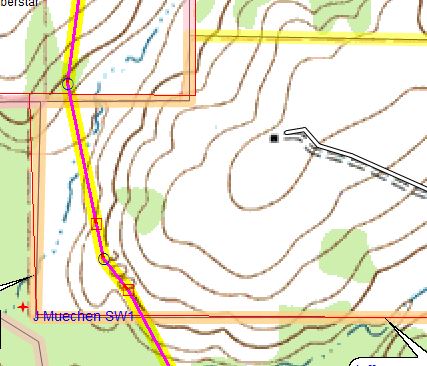

From the coast to the Cap Rock, Texas has more than 200 treasure legends. One cache is supposed to sit beneath a private 400-acre lake in the heart of the Sabine River bottom near Tatum. The ancient river snakes through Panola County near Carthage and divides Texas from Louisiana, but here, deep in this forest of pine and oak, it has always had a mind of its own.

When this land was young, the river changed its course, leaving behind slivers of spring-fed water that locals call "oxbow lakes" or "lost lakes," including Hendrick's. The Sabine is a stone's throw away; some say that the ancient river and its fickle ghosts stand sentinel over any treasure that may be hidden there. In August, the thick air is filled with the shrill whine of mosquitoes. Cypress trees on the steep banks stretch their leafy arms skyward. A silvery scum tops much of the lake's bourbon-colored water and toothy alligator gar, snapping turtles and black bass swim its murky depths.

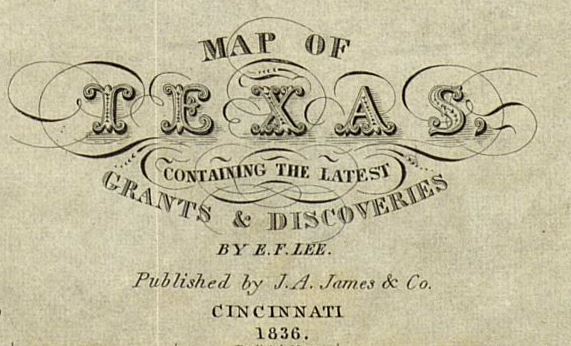

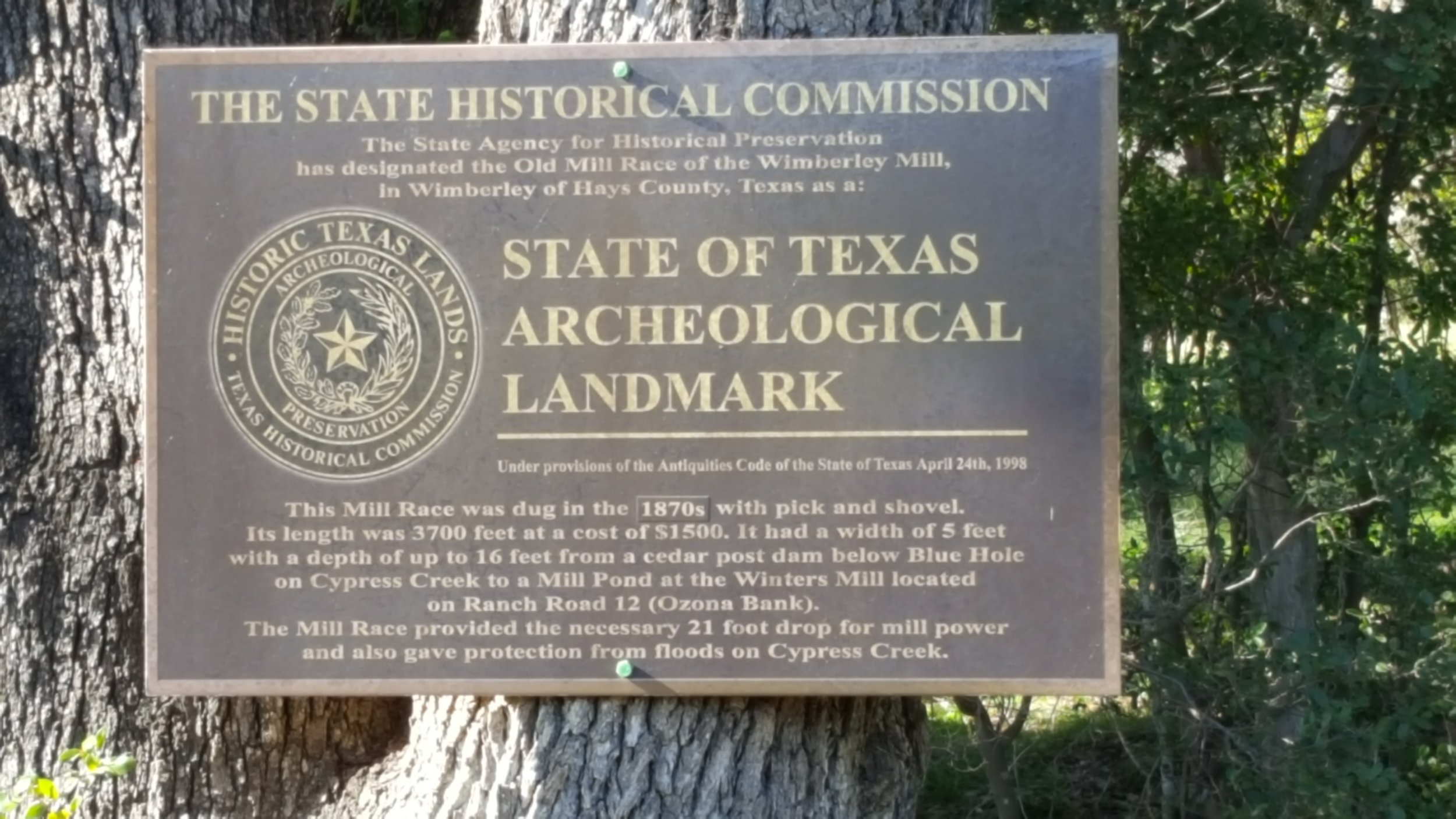

Occasionally, an oil field truck whizzes up the clay lane that was once a part of an early roadway called Trammel's Trace, splashing mud from the recent rains. According to legend it was here in 1812 or 1816, or maybe 1818, along this half-mile stretch of water, that Jean Lafitte's men, afraid that they were about to be ambushed, pushed several wagons loaded with silver ingots into the muddy water.

The wagons and the silver bars quickly disappeared into the soupy depths and the thick layer of bottom silt. Only one man lived to tell the tale -- the others were slaughtered.

No one knows for sure if that lone survivor came back to recover the silver, but it is clear that by 1884, treasure hunters were feverishly trying to drain the lake. The Galveston Daily News sniffed at the effort. "They should transfer their operations to the Gulf of Mexico. A good deal of wealth has been left under its waters by shipwrecks," wrote one reporter.

Before the treasure hunters could drain the lake completely, a storm tracked across the countryside and the angry Sabine River overflowed its banks and coursed through the lake, filling it to overflowing.

Treasure and the river

Decades rolled past. Teddy Roosevelt stormed San Juan Hill. The Wright brothers flew. Ford automobiles became the rage. The stock market crashed. Prohibition came and went. Women got the right to vote. The world went to war twice.

And then came the prosperous days of the 1950s. Treasure magazines became popular and searching for lost gold became an interesting distraction. True West Magazine printed a story about the long-forgotten Hendrick's Lake silver, and treasure hunters flocked to Carthage and Tatum, says Gary Pinkerton who is writing a book about Trammel's Trace and the legend.

Dallas oilman Henry SoRelle and his brother A.C. SoRelle Jr. were part of the onslaught.

"I was about 25 then, and my brother was 10 years older," SoRelle says. In those years, the younger SoRelle was the land man for the family's Houston-based oil business. In no time, he had inked a lease from the landowners, which included former Panola County Sheriff Corbett Akins; his chief deputy, "Cush" Reeves; and Peter Walker Adams, who wore overalls, carried an impressive knife and rented fishing boats at one end of the lake.

The SoRelle brothers had a large metal detector that they hauled around the lake. "All of a sudden we got a hit," SoRelle remembers, his blue eyes shining, his fist clenched in victory. "We thought we could get a scuba diver to just dive down there and get it, but we found out the lake was very deep in silt and the water was so murky you couldn't see very far." He leans back in his office chair, smiling. "That didn't work," he says.

They brought in a giant crane and attached a drag bucket to the cable, but the gooey bottom slime was too much for the machine, and the treasure was too far from the bank. More than once the crane almost toppled into the water. Soon the crane operator, fearful that he might lose his machine and his livelihood, went home. But the SoRelles weren't ready to call it quits.

They built a raft with a hole in the center and sank large pipes into the goop on the lake bottom. They lowered another contraption through the pipe to the lake floor. A light would come on when a probe hit metal. "It did light up, too," SoRelle says. Encouraged, the men worked on.

"We had a drill, which we turned manually," SoRelle says. The men laid into the chore with gusto, but there was too much gumbo silt to move, he says. Running low on cash, the brothers decided they needed a break -- and a better plan.

They headed for their Houston homes and a few days of rest, leaving the raft anchored in the center of the lake, confident that the sheriff would protect their find.

They hadn't been gone long when a great storm raced across Panola County. The rain came in torrents, and the Sabine River swirled over its banks. The river swept across the little lake, smashing the raft and washing away every shred of evidence that the SoRelle brothers had ever been there.

SoRelle shrugs at the memory. The brothers left the treasure for someone else to find, he says.

Wheel of fortune

Barnie Waldrop, a fix-it man and inventor who worked in a radio repair shop in Carthage, was the next man to look.

Waldrop had studied the legend -- and the lake -- for years and had long ago struck a deal with the landowners to search for the treasure with a water-resistant metal-detecting apparatus he perfected himself. In 1958, he finally had his chance to search.

"Mr. Barnie was kind of quiet. He tended to his own business ... He wore khakis and was neat about his appearance," says Brodie Akins, 69, son of the old sheriff who owned part of the lake. "If you needed something fixed, why you took it to Mr. Barnie and he'd fix it up, but he wasn't jokey."

Akins and his late sister's three sons inherited his daddy's portion of the land, but he remembers that he was in high school the summer of the treasure hunt. "Daddy never doubted Mr. Barnie," he says. Young Akins was there the day the dragline hauled up an ancient metal wagon wheel rim of the sort used on Mexican ox carts a century or more earlier.

"That ol' wheel came out of the water all covered with slime," he says. "Everything shut down. The operator got off the dragline. We all thought, oh yeah, we going to hit it now. We on to something now, but that ol' wheel is the only thing they ever found," he says.

The sticky silt lay more than a dozen feet deep on the lake's lignite bottom, and like other treasure hunters before him, Waldrop decided he had to move that mud to find the silver.

He tried dynamite. "Snakes and fish and all kinds of things floated to the top," says Waldrop's son Philip Waldrop, 62, of Carthage. He was often at the lake with his sister Diana. In fact, she is the one who dropped the dynamite charge into the lake that day.

Nothing worked. If the treasure was there, it remained hidden in the slime. Barnie Waldrop swallowed any disappointment he felt and soldiered on, writing at least one article for a treasure magazine and searching for the lost silver several more times over the years.

An occasional newspaper article kept the story alive and throughout the 1960s treasure hunters found their way to Hendrick's Lake, but none matched the expeditions launched by the SoRelle brothers or Barnie Waldrop.

A few years ago, treasure hunters, certain that the lake had silted in over time, decided the silver must now lay under dry land. They punched holes in a pasture near the lake but found no treasure, Philip Waldrop says.

The secret at the bottom

So is there treasure at Hendrick's Lake?

"Some thinks there is. Some thinks there isn't," Akins says.

He rocks back in a squeaky office chair and thinks a moment. "I'm not a believer in jinxes," he says, "but I've seen these people that have hunted. They've come in here with a good bit of money and they claim they get real close to it, and then that ol' river comes up and floods everything and they're right back to zero. I've seen it happen too many times.

"I think there may be a jinx on it -- but I'll say it's a good legend."

And what of the fishermen's silver bars found so long ago? That never happened, Philip Waldrop says. "It just was something to add to the story," he says.

Back in his Dallas office, SoRelle considers the treasure he's not thought of in years. "The only way to get to the treasure is to drain the lake," he declares, "but every time someone would try ... well, it's just amazing, there would be a storm. The river would take over."

If he owned the lake, he'd drain it for sure. "There's something there," he says and taps his desktop -- and his blue eyes dance.

That ol' wheel came out of the water all covered with slime.

Every time someone would try ... the river would take over.

Snakes and fish and all kinds of things floated to the top.

Three tips for beginning treasure hounds

1. Peruse the Internet ( www.legendsofamerica.com; www.treasurefish.com), but invest in a copy of Coronado's Children by J. Frank Dobie (University of Texas Press) and W.C. Jameson's Buried Treasures of Texas (August House Publishers Inc.) There are other Texas treasure books on the market, but these two little volumes cover most of the major stories.

2. Research the treasure that tickles your fancy and determine where it might be located; then contact someone in the area to help narrow your search area.

3. Remember that most treasure sites are on private property and you'll need permission to search before you get there.

Three more Texas treasure legends

Red River gold

The legend: In 1894 four men robbed the bank at Bowie and made off with $10,000 in $20 gold pieces and $18,000 in currency. They rode north toward the safety of Indian Territory, but when they got to the Red River they found the water too high to cross. They camped near a grove of trees for the night.

Meanwhile, the Bowie sheriff telegraphed a U.S. marshal named Palmore and told him to watch for the outlaws. Palmore apprehended the outlaws at the river crossing the next day and hauled them off to the hanging judge in Fort Smith, Ark. Before the men were executed, one told Palmore that the gold was buried at the campsite -- and then he winked.

The location: The gold is said to be on the Texas side of the Red River at the confluence of the Little Wichita River.

Sam Bass' cache

The legend: Sam Bass and his outlaw gang robbed many trains and stagecoaches and stashed the loot in several locations. In 1877, it is said, they robbed a Nebraska train of a fortune in newly minted gold coins. The robbers divided the gold and rode off in different directions. Young Bass made his way to Denton and hid his portion of the prize.

Around 1900, a farmer near Springtown, northwest of Fort Worth, found a trunk filled with 1877 gold coins that many believe is part of the treasure -- but only a portion.

The location: Treasure hunters say Bass' part of the gold is hidden at Cove Hollow, a brushy ravine shot through with shallow caves about 30 miles from Denton.

The lost San Saba silver mine

The legend: For more than two centuries, this lost mine with its rich vein of silver has been the Holy Grail of Texas treasure seekers. In 1756, Don Bernardo de Miranda, a Mexican official, learned of the mine from an Apache guide. It's said that American Indians worked the mine, often trading the ore in San Antonio. Over the decades, many men looked for the mine, including Jim Bowie a few years before he came to the Alamo.

The location: Somewhere near Menard, on the San Saba or Llano rivers.

News researcher Marcia Melton contributed to this report.

------

rog@star-telegram.com Mary Rogers, 817-390-7745

Read more at http://www.redorbit.com/news/science/1067673/tales_of_spanish_silver_lure_treasure_hunters_to_an_east/#t3KpH0Kub7HeJCt3.99